A Historic Day for Physician Well-Being in Idaho

by Steven Reames

June 15, 2023

Most revolutionary changes happen at an evolutionary pace. So, when a moment of “punctuated equilibrium” takes place in real-time, it is worth calling out and putting in the fossil record, as it were. Last Friday, June 9 was one of those moments for the advancement of physicians' well-being in Idaho, along with many others’. The assurance of "public health, safety and welfare" will no longer be protected just through proper credentialing and vetting. We have crossed the threshold where the active and intentional promotion and protection of physician will-being is becoming as important as "protecting against snake oil salesmen" and issuing stipulations and orders.

Drs. Lorna Breen and Maurice “Mo” Brown

On the fifth floor of St. Luke’s Health System's Anderson Center, thirty local representatives from a variety of healthcare institutions gathered to work on reducing mental health stigma for physicians. Specifically, we attacked the issue of probing mental health, addiction, and substance use history questions that physicians and other clinicians have always had to answer to get licensed, credentialed, and employed. Research over the past 10 years has raised doubts as to whether questions actually promote patient safety while documenting that they frequently degrade the willingness of physicians to seek treatment when they need it.

Our workshop facilitator was J. Corey Feist, the president of the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes' Foundation, based in Virginia. It started after his sister-in-law, a New York City emergency room physician, ended her own life during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Serving when that tidal wave of human suffering hit the Eastern Seaboard quickly overwhelmed her, but she avoided seeking help explicitly because of the fear of losing her medical license “if people found out.”

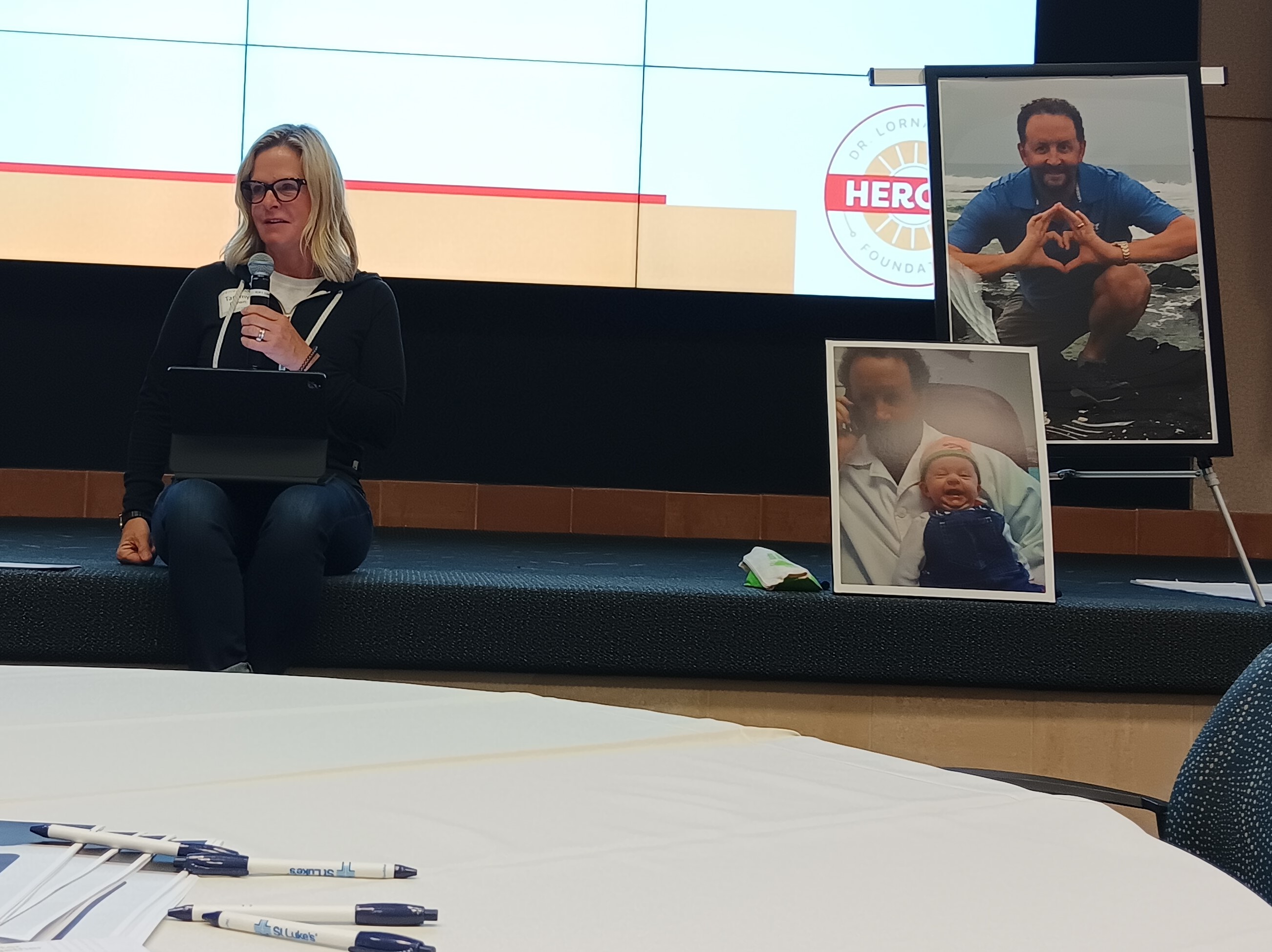

Corey related Dr. Breen’s story along with recent research to emphasize that such fears are prevalent among physicians. Tammy Brown from Teton Valley, Idaho also shared the about her physician husband, orthopedist Maurice “Mo” Brown, who died last August. Sitting next to a picture of him on the stage, Tammy described how his mental health declined during 2020.

Tammy Brown describes the depression and isolation that her late husband, Teton Valley orthopedist Maurice “Mo” Brown, had over seeking mental health or substance abuse treatment because of the fear of the loss of licensure.

She urged him to get treatment, called the Idaho State Board of Medicine (IBOM) for a facility referral, and was confused about the options presented. In her words, "During the COVID pandemic, Mo experienced increased stress and depressive, isolating thoughts. He began to self-medicate with alcohol. He feared that "mental health or substance abuse" treatment could result in public humiliation and losing his job and licensure. In the end when he most needed help, he saw no other option than ending his life."

When I spoke with Mrs. Brown for the first time this winter, she was surprised to find out two things about IBOM. First, the Board had already changed its renewal form in the past few years so that it wasn’t overly invasive about mental health. Second, they have long had a confidential mechanism that allows physicians to keep their medical license while working to recover from substance/alcohol abuse: the Physicians Recovery Network (PRN) which became the Health Professionals Recovery Program (HPRP) in April this year.

Changes in Idaho Came Slowly

When I first arrived at Ada County Medical Society (ACMS) in 2014, I began to hear quiet admissions from physicians such as, “When I need mental health care, I go out of state, use a different name, and pay cash so it never hits my insurance.” Multiple research articles eventually began to document these widespread fears and attitudes of doctors throughout the 2010s. One article’s main title captures the concerns succinctly: “‘I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record.’”[1] This was a big factor in why ACMS started its Physician Vitality Program in 2016.

In April 2018, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) validated these concerns in its report from its Physician Wellness and Burnout Workgroup and adopted landmark recommendations as its policy. It requested “that state medical boards review their medical licensure (and renewal) applications and evaluate whether it is necessary to include probing questions about a physician applicant’s mental health, addiction, or substance use.”[2]

In Idaho, we can have some satisfaction knowing that the organized medical community had begun efforts to make such changes the prior year. At the July 2017 Idaho Medical Association’s (IMA) House of Delegates (HOD), emergency medicine physician Heather Hammerstedt, MD, MPH presented a resolution that stated in part:

"The IMA will work with stakeholders to improve established policies, rules and procedures and the communication about them for the evaluation of a physician’s mental health during licensure, credentialing and hiring or retention processes to reduce the stigma and potential for inappropriate negative professional consequences for physicians who disclose mental health conditions.”

The resolution, which was co-sponsored by ACMS, Idaho Academy of Family Physicians, Idaho Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, and Idaho Psychiatric Association, was referred by the HOD to the IMA Board for further action.

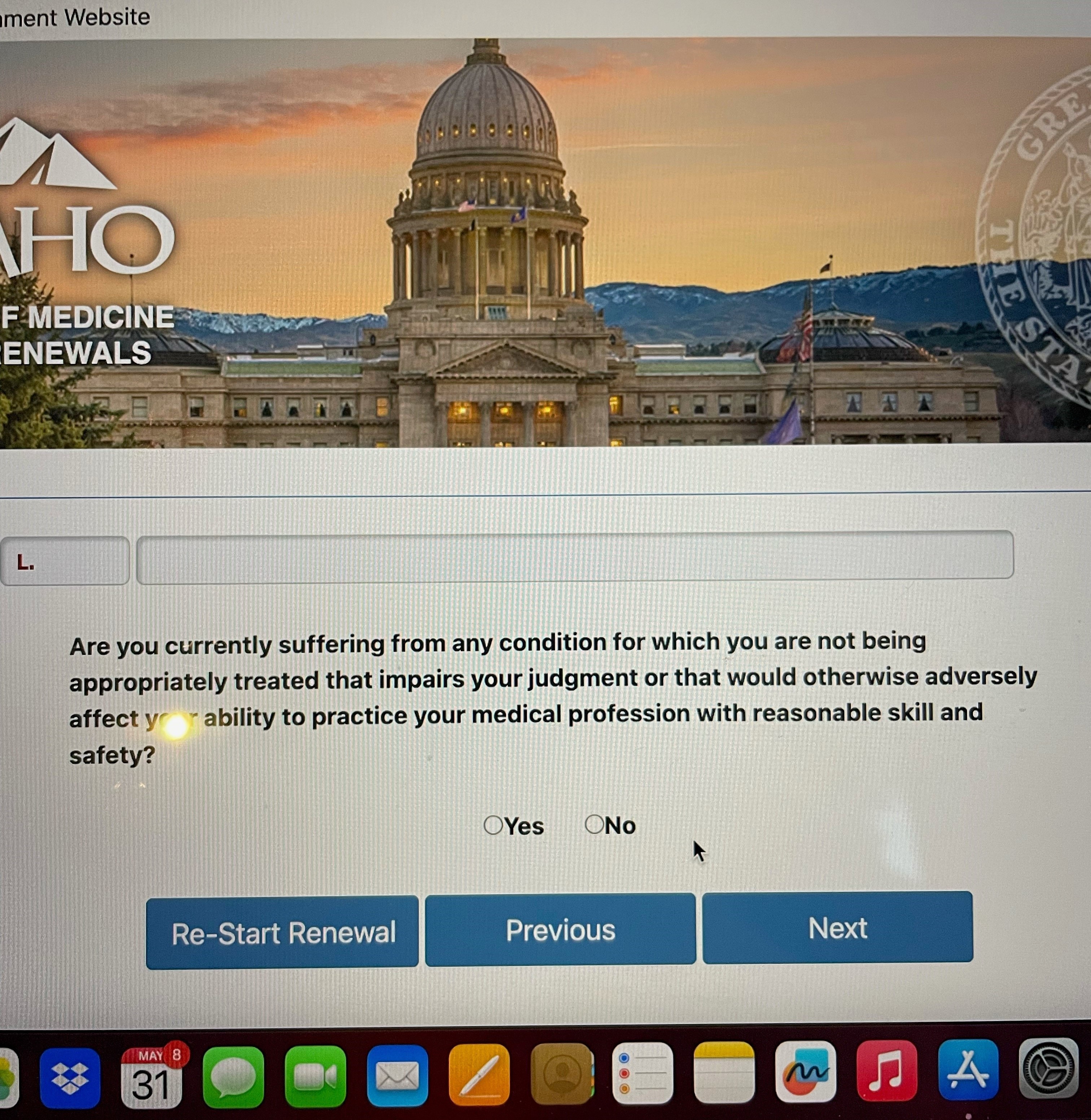

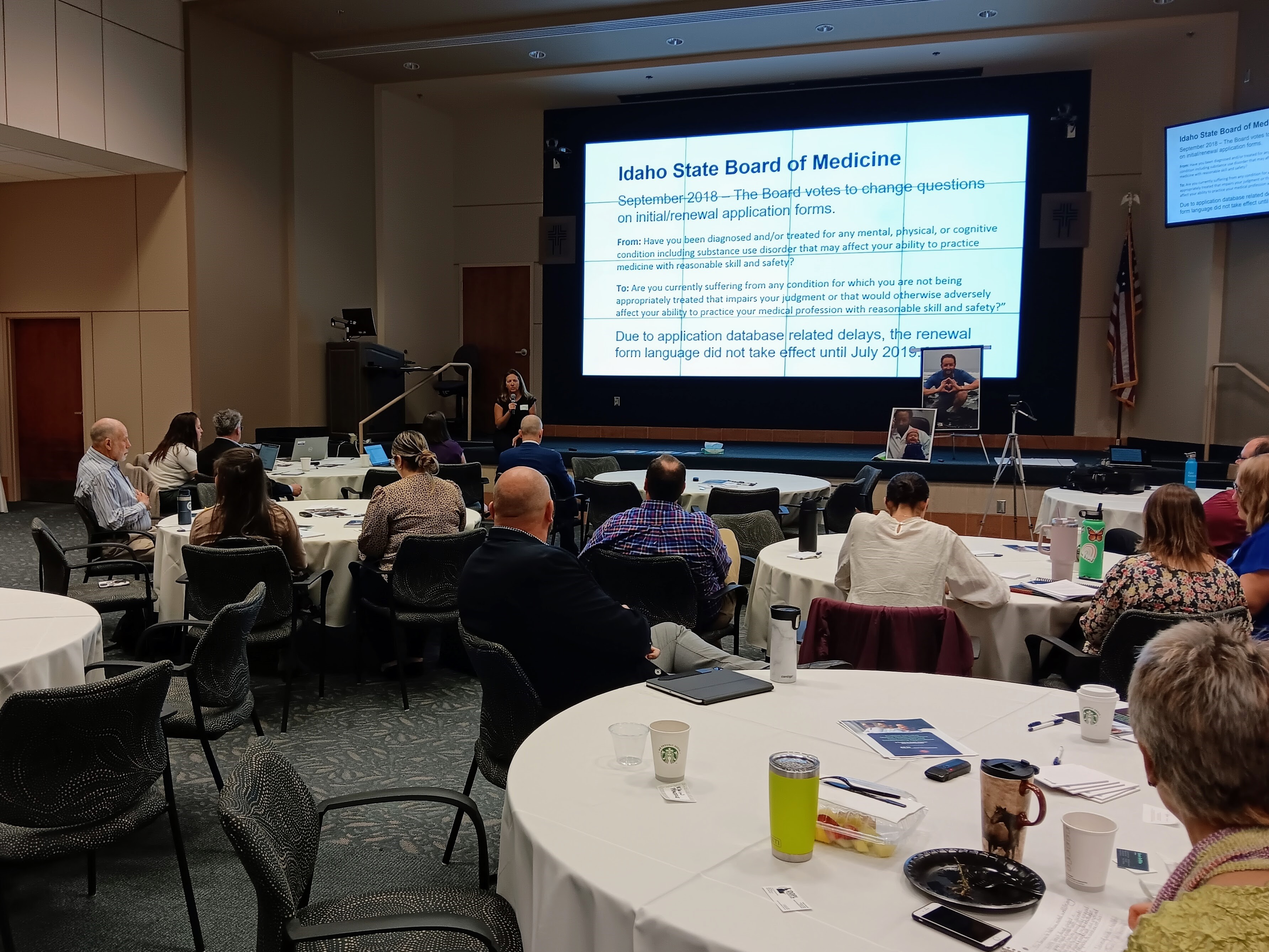

The following July, IBOM voted to change questions on its initial application and renewal forms from: “Have you been diagnosed and/or treated for any mental, physical, or cognitive condition including substance use disorder that may affect your ability to practice medicine with reasonable skill and safety?” to “Are you currently suffering from any condition for which you are not being appropriately treated that impairs your judgment or that would otherwise adversely affect your ability to practice your medical profession with reasonable skill and safety?"[3]

An ACMS member sent a screenshot of the new renewal question just last week: Good News! This year’s IDAHO BOM renewal language is even better!

Implementation of the change was not immediate, however, due to issues related to IBOM’s database and synchronization with FSMB's Universal Application form. The renewal language was changed in July 2019, followed by the initial application form during the summer of 2020. Clear communication with licensees and the public about the changes has also been a challenge. Idaho’s form updates were not picked up in two separate national surveys in 2020 and 2021.[4][5] Other questions related to substance use still remain and improvements around more pro-treatment-seeking language can be added.

Dr. Brown’s situation shows, however, that if “old-school” language remains on any application, form, or contract required of a physician, it almost negates the fact that changes were made at the Board level. This is why doctors and administrators came out last week from St. Luke’s and Saint Alphonsus Health Systems, Pacific Source Health Plans, Idaho Hospital Association, Idaho Medical Association, Desert Sage Health Clinics, independent Treasure Valley medical practices, IMA, and the Board.

A Swell of Commitment to Transformation

Mrs. Brown started to leave the stage and I asked her to leave Mo’s picture up to remind us why this work was so important. She was followed by Nicki Chopski, PharmD, the Health Professions Bureau Chief at the Idaho Department of Professional Licensing, who also serves as executive officer for the Boards of Medicine, Nursing, and Pharmacy. In addition to sharing the history of the changes above, she also stated a desire to propagate them across multiple licensing boards in the health division and to further reduce administrative burdens for clinicians.

By the time we got to work on the issue that morning, we had only 90 minutes left, and I began to feel a little worried we were not going to accomplish much. But Corey led us quickly through breakout sessions to audit forms for troubling language, make proposals for change, and think about how to communicate to those affected. With just 15 minutes left, he called for public commitments along with timelines for changes.

Idaho Department of Professional Licensure executive officer Nicki Chopski, PharmD shared Idaho Board of Medicine's progress on changing the licensure questions.

The first representative stood up and said, “By the end of today, this question on our credentialing form will change and the biggest obstacle we have is converting the PDF document into an editable Word document.” He then threw down the gauntlet to everybody else in the room.

Another organization followed and said they would move to an attestation of fitness for duty rather than a question asking about mental health history. A third institution reported it had already made such changes two years ago and that everybody had been recredentialed with the new question since then.[6] As if to put the cherry on top, Ms. Chopski stood up and ticked off half a dozen action items she intended to work on at IBOM and within DOPL.

Suddenly I realized that we were “in the room where it happens” and goosebumps spread across my arm.

While these changes have been years in the making and will still take time to become pervasive, the lasting impact will be felt generationally. Moreover, it will be the conversations that follow at all levels because of the shifting medical culture where eventually nobody must feel like they need to hide their brokenness.

The reduction of mental health stigma by whatever means possible, along with the promotion and support of personal well-being among all healthcare team members, must be seen as a foundation for patient safety and high-quality medical care. Together, we can elevate what is best for everyone: the encouragement to seek help to care for one’s own needs. After all, physicians are humans too.

References

[1] Gold KJ, Andrew LB, Goldman EB, Schwenk TL. "I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record": A survey of female physicians on mental health diagnosis, treatment, and reporting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016 Nov-Dec;43:51-57. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.09.004. Epub 2016 Sep 15. PMID: 27796258.

See next reference for links to much more research on this issue.

[2] https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/policy-on-wellness-and-burnout.pdf

[3] McCluskey, David “Recent changes to the Idaho Board of Medicine Application Forms,” Idaho State Board of Medicine, The Report (Newsletter), Fall 2019

[4] Saddawi-Konefka D, Brown A, Eisenhart I, Hicks K, Barrett E, Gold JA.

Consistency Between State Medical License Applications and Recommendations Regarding Physician Mental Health. JAMA. Published May 18, 2021. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.2275

[5] https://drlornabreen.org/identifying-the-states/ (accessed April 2023). It should be noted that as of their May 1, 2023, update, Idaho is now regarded as consistent with FSMB recommendations.

[6] This question is a hybrid between proactive treatment-seeking messaging, with clarification of definitions, and attestation of fitness for duty. "We are aware that our clinicians may experience the need for physical or mental health care and encourage seeking such care. When asking about current impairment, we are specifically asking about any current impairment to your practice of medicine, not diagnosis or treatment of health conditions. Are you currently physically and mentally available to perform all of the privileges you are requesting?”

Copyright 2023 Ada County Medical Society

|