By Steven Reames, Executive Director, Ada County Medical Society

I was listening to an interview on NPR this spring with Kevin Roose, a New York Times tech columnist. He was speaking about his new book and how humans need to “futureproof” themselves with respect to artificial intelligence. This quote caught my attention:

“We've been telling people to become as productive as possible to optimize their lives, to squeeze out all the inefficiency and spend their time as effectively as possible, in essence, to become more like machines. And really, what we should be teaching people is to be more like humans, to do the things that machines can't do.”[i]

Unfortunately, this rings so true when I think about the industrialization of medicine that has dominated healthcare for the past 40 years. Since the 1980s, the Golden Age of Doctoring has been dying a fast death as US health care has been transformed into a “corporatized system dominated by increasingly concentrated and globalized financial and industrial interests.”[ii] In its wake, doctors have had more and more autonomy stripped away from their clinical decision-making in the name of “evidence-based medicine” and productivity requirements. Overall, have we seen any healthcare dollars saved because of this? Mmmm….

Now please, don’t get me wrong: we need medical care based on rigorous studies so that we don’t throw away unnecessary money, time, or lives in the practice of pseudo-medicine. We also need to eliminate medical care that is provided purely to pad the pocketbooks of investors and the need to play defense from malpractice lawsuits. But what is slowly coming about might be a healthcare assembly line staffed by production physicians who are merely technicians of science.

It is only inevitable what this has resulted in. When creativity is crushed out of people, it bruises an aspect of their dignity as human beings. It stifles innovation and keeps people within the boxy confines of predetermined algorithms. As we get used to this, it may not be too long until we may be tempted to hand over all “creative” thinking and medical diagnostic to artificial intelligence.

It has already been demonstrated that AI produces faster, better, and more accurate radiological diagnostics than humans.[iii] Maybe that’s a good thing: it is mundane, routine, and it might be nice to get physicians out of dark rooms looking at computer screens all day so long as they have other jobs to take.

Right around the corner are also opportunities that could save some mind-numbing time-wasters for more physicians. If you do a quick search on GPT-3 technology, you will find anybody can subscribe to services that will write blog entries, real estate listings, computer code, and even draw rudimentary artwork based on natural language prompts. If you read The Guardian article[iv] written by this technology – albeit with edits by humans – you can envision a day when your medical note could be at least drafted by a computer for your review and approval. If this provided you more time to connect with patients, great. But it always seems that what starts slowly with “this will make the practice of medicine better” ends up biting physicians on the backend.

The practice of medicine is both technical and artistic. Even if the technical skills are all in place no later than the mid-30s, it still takes a lifetime of practice to master the art of serving patients well. Good art takes time, effort, and space to try something you have not tried before. Thus, it is no wonder why there is tremendous hopelessness among industry-employed physicians: they simply are not allowed to use both their acquired medical skills and their God-given talent in their day-to-day work.

Funny anecdote: a frequent piece of feedback we receive on evaluations following our annual Winter Clinics CME conference is “more clinical pearls.” This tells me that physicians are hungry for those “small bits of free-standing, clinically relevant information based on experience or observation… part of the vast domain of experience-based medicine, (which) can be helpful in dealing with clinical problems for which controlled data do not exist.”[v] It gives me hope that our doctors are still looking for answers that go beyond something that can be fed into or provided by a computer.

Which brings me back to my main point and a series of questions: how might we apply Roose’s guidance about keeping physicians from being replaced by AI?

- How do we use medical AI and quantum computing to their fullest to help drive the best clinical decisions or eliminate unnecessary tasks without sacrificing humanity in the process?

- What behaviors, attitudes, and habits can we adopt to guard the humanity of medicine?

- What should we be teaching in medical school that machines cannot (yet) do?

- How do we help investors, boards, and C-suite leaders see the value of physicians connecting as people and not merely pushers of pills and procedures?

These are questions that rarely get asked in a local community and are easily left to think tanks and philosophy professors. But I hope our local and state medical community will not let somebody in New York, Washington DC, or Palo Alto do all the thinking on big topics like this. The ethos of medicine must be introduced into conversations with AI developers and business leaders now or it will be very difficult to stand against its adoption when it gets sexy and smart enough to deploy. But if physicians let somebody else do the thinking for them on important questions like this, perhaps they deserve to be replaced by robots after all.

[i] Kevin Roose's 'Futureproof' Offers Rules to Thrive In The Age Of Automation: NPR

[ii] The end of the golden age of doctoring - PubMed (nih.gov)

[iii] Wait. Will AI Replace Radiologists After All? (radiologybusiness.com)

[iv] A robot wrote this entire article. Are you scared yet, human? | GPT-3 | The Guardian

[v] What is a clinical pearl and what is its role in medical education? - PubMed (nih.gov)

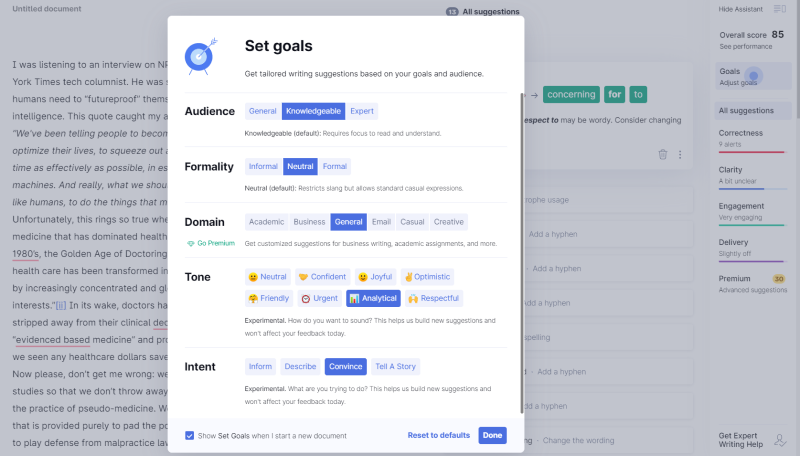

P.S. in an ironic twist, I ran my final draft through Grammerly, an AI writing assistant that makes suggestions based on grammatical and stylistic conventions that you can dial in based on your intent. Aside from the typo identification, which was helpful, I specifically chose to ignore some of its suggestions to keep my own artistic voice intact.